In-Person

China Institute Gallery Presents Shan Shui Reboot: Re-envisioning Landscape For a Changing World

March 7, 2024 - July 7, 2024

In-Person

AAPI Month Program

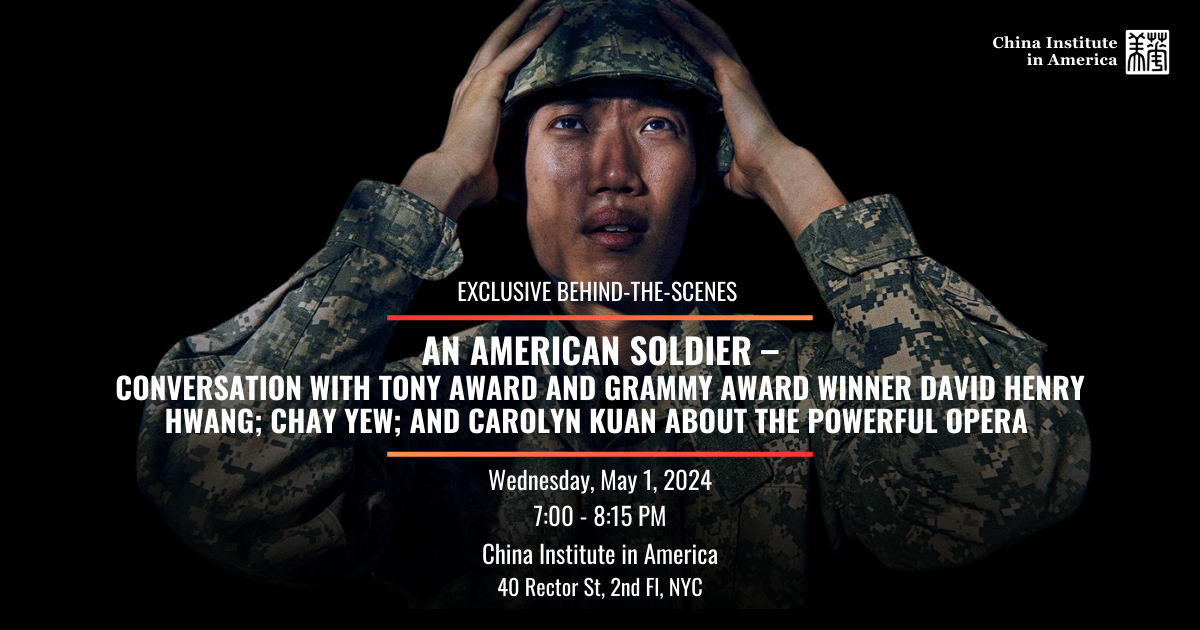

An American Solider —

Conversation with Tony Award and Grammy Award Winner David Henry HWANG; Chay YEW; and Carolyn KUAN About the Powerful Opera Commemorating a Soldier’s Racially Charged Tragedy

Wednesday, May 1, 2024 | 7:00 - 8:15 PM ET

In-Person

AAPI Month Program

Meet the Artist

Exploring the Creative World of Yang Yongliang

Tuesday, May 7, 2024 | 6:00 - 7:00 PM ET

In-Person

AAPI Month Program

Visionary Dialogues:

Shan Weijian on Crafting the Future of Global Investments and China’s Economy

Friday, May 17, 2024 | 6:00 - 7:30 PM ET

In-Person

AAPI Month Program

Tea For Harmony

Xinyang Maojian Tea Cultural Fair

Thursday, May 23, 2024 | 4:00 - 6:00 PM ET

In-Person

AAPI Month Program

TAN DUN in CONCERT

with the Dunhuang Ancient Music Ensemble

Sunday, May 12, 2024 | 6:00 - 7:30 PM

Join us on Sunday, May 12 from 6:00-7:30 pm for a rare opportunity to hear composer/conductor Tan Dun perform new musical pieces with the Dunhuang Ancient Music Ensemble. Tan Dun will discuss his creative process and inspirations throughout the program.

Tickets on sale now!

Online

Lunch and Learn

Friday, May 3 | 12:00 - 1:00 PM EDT

Partner Event

The Serica Initiative

AAPI Women's Gala 2024

Tuesday, May 14, 2024

Tribeca 360, NYC

Upcoming Events

A history of sharing culture

Founded in New York City in 1926 by American educators John Dewey, Paul Monroe, and Chinese scholars Hu Shi (胡適) and Kuo Ping-Wen (郭秉文), China Institute in America is an internationally-renowned U.S. nonprofit organization dedicated to deepening the world’s understanding of China through programs in art, business, culinary, culture, and education.

A history of sharing culture

Founded in 1926 by American educators John Dewey, Paul Monroe, and Chinese diplomats Hu Shi (胡適) and Kuo Ping-Wen (郭秉文), China Institute is the oldest bicultural, non-profit organization in America to focus exclusively on China.

School of Chinese Studies

Culinary Center

Soon to debut in 2024, the Chinese Culinary Center at China Institute in America was created with a vision to highlight the diverse and long-standing heritage of authentic Chinese cuisine, and to enhance the appreciation of Chinese cuisine as a new conduit of cross-cultural exchange in America, and internationally.